Sockets and the socket API are used to send messages across a network. They provide a form of inter-process communication (IPC). The network can be a logical, local network to the computer, or one that’s physically connected to an external network, with its own connections to other networks. The obvious example is the Internet, which you connect to via your ISP.

In this tutorial, you’ll create:

- A simple socket server and client

- An improved version that handles multiple connections simultaneously

- A server-client application that functions like a full-fledged socket application, complete with its own custom header and content

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand how to use the main functions and methods in Python’s socket module to write your own client-server applications. You’ll know how to use a custom class to send messages and data between endpoints, which you can build upon and utilize for your own applications.

The examples in this tutorial require Python 3.6 or above, and have been tested using Python 3.10. To get the most out of this tutorial, it’s best to download the source code and have it on hand for reference while reading:

Background #

Sockets have a long history. Their use originated with ARPANET in 1971 and later became an API in the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) operating system released in 1983 called Berkeley sockets.

When the Internet took off in the 1990s with the World Wide Web, so did network programming. Web servers and browsers weren’t the only applications taking advantage of newly connected networks and using sockets. Client-server applications of all types and sizes came into widespread use.

Today, although the underlying protocols used by the socket API have evolved over the years, and new ones have developed, the low-level API has remained the same.

The most common type of socket applications are client-server applications, where one side acts as the server and waits for connections from clients. This is the type of application that you’ll be creating in this tutorial. More specifically, you’ll focus on the socket API for Internet sockets, sometimes called Berkeley or BSD sockets. There are also Unix domain sockets, which can only be used to communicate between processes on the same host.

Socket API Overview #

Python’s socket module provides an interface to the Berkeley sockets API. This is the module that you’ll use in this tutorial.

The primary socket API functions and methods in this module are:

socket().bind().listen().accept().connect().connect_ex().send().recv().close()

Python provides a convenient and consistent API that maps directly to system calls, their C counterparts. In the next section, you’ll learn how these are used together.

As part of its standard library, Python also has classes that make using these low-level socket functions easier. Although it’s not covered in this tutorial, you can check out the socketserver module, a framework for network servers. There are also many modules available that implement higher-level Internet protocols like HTTP and SMTP. For an overview, see Internet Protocols and Support.

TCP Sockets #

You’re going to create a socket object using socket.socket(), specifying the socket type as socket.SOCK_STREAM. When you do that, the default protocol that’s used is the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). This is a good default and probably what you want.

Why should you use TCP? The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP):

- Is reliable: Packets dropped in the network are detected and retransmitted by the sender.

- Has in-order data delivery: Data is read by your application in the order it was written by the sender.

In contrast, User Datagram Protocol (UDP) sockets created with socket.SOCK_DGRAM aren’t reliable, and data read by the receiver can be out-of-order from the sender’s writes.

Why is this important? Networks are a best-effort delivery system. There’s no guarantee that your data will reach its destination or that you’ll receive what’s been sent to you.

Network devices, such as routers and switches, have finite bandwidth available and come with their own inherent system limitations. They have CPUs, memory, buses, and interface packet buffers, just like your clients and servers. TCP relieves you from having to worry about packet loss, out-of-order data arrival, and other pitfalls that invariably happen when you’re communicating across a network.

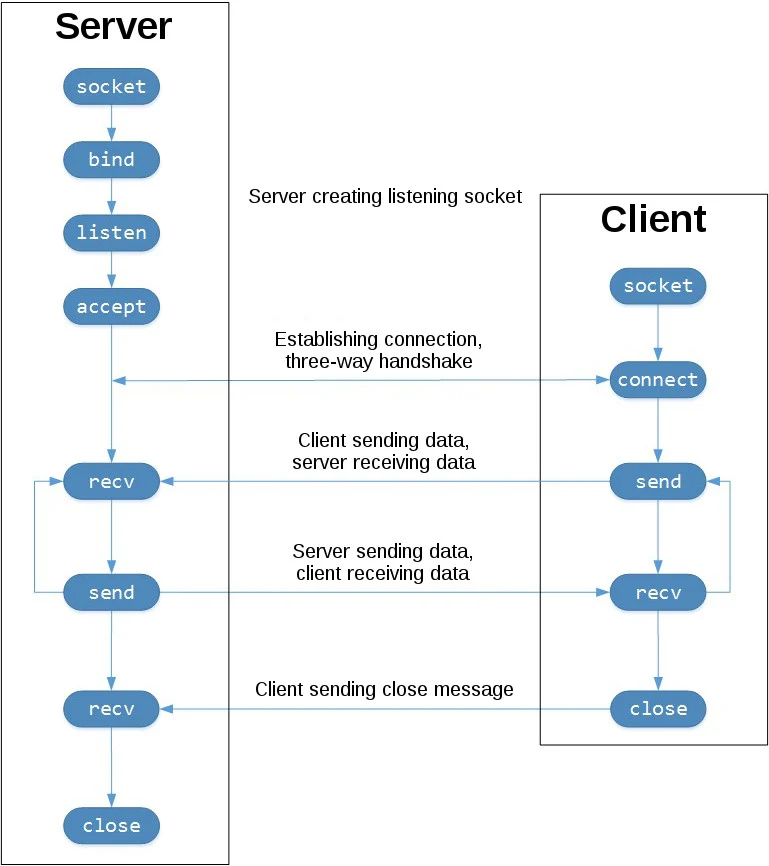

To better understand this, check out the sequence of socket API calls and data flow for TCP:

The left-hand column represents the server. On the right-hand side is the client.

Starting in the top left-hand column, note the API calls that the server makes to set up a “listening” socket:

socket().bind().listen().accept()

A listening socket does just what its name suggests. It listens for connections from clients. When a client connects, the server calls .accept() to accept, or complete, the connection.

The client calls .connect() to establish a connection to the server and initiate the three-way handshake. The handshake step is important because it ensures that each side of the connection is reachable in the network, in other words that the client can reach the server and vice-versa. It may be that only one host, client, or server can reach the other.

In the middle is the round-trip section, where data is exchanged between the client and server using calls to .send() and .recv().

At the bottom, the client and server close their respective sockets.

Echo Client and Server #

Now that you’ve gotten an overview of the socket API and how the client and server communicate, you’re ready to create your first client and server. You’ll begin with a simple implementation. The server will simply echo whatever it receives back to the client.

Echo Server #

Here’s the server:

# echo-server.py

import socket

HOST = "127.0.0.1" # Standard loopback interface address (localhost)

PORT = 65432 # Port to listen on (non-privileged ports are > 1023)

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

s.listen()

conn, addr = s.accept()

with conn:

print(f"Connected by {addr}")

while True:

data = conn.recv(1024)

if not data:

break

conn.sendall(data)Okay, so what exactly is happening in the API call?

socket.socket() creates a socket object that supports the context manager type, so you can use it in a with statement. There’s no need to call s.close():

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

pass # Use the socket object without calling s.close().The arguments passed to socket() are constants used to specify the address family and socket type. AF_INET is the Internet address family for IPv4. SOCK_STREAM is the socket type for TCP, the protocol that will be used to transport messages in the network.

The .bind() method is used to associate the socket with a specific network interface and port number:

# echo-server.py

# ...

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

# ...The values passed to .bind() depend on the address family of the socket. In this example, you’re using socket.AF_INET (IPv4). So it expects a two-tuple: (host, port).

host can be a hostname, IP address, or empty string. If an IP address is used, host should be an IPv4-formatted address string. The IP address 127.0.0.1 is the standard IPv4 address for the loopback interface, so only processes on the host will be able to connect to the server. If you pass an empty string, the server will accept connections on all available IPv4 interfaces.

port represents the TCP port number to accept connections on from clients. It should be an integer from 1 to 65535, as 0 is reserved. Some systems may require superuser privileges if the port number is less than 1024.

Here’s a note on using hostnames with .bind():

“If you use a hostname in the host portion of IPv4/v6 socket address, the program may show a non-deterministic behavior, as Python uses the first address returned from the DNS resolution. The socket address will be resolved differently into an actual IPv4/v6 address, depending on the results from DNS resolution and/or the host configuration. For deterministic behavior use a numeric address in host portion.” (Source)

You’ll learn more about this later, in Using Hostnames. For now, just understand that when using a hostname, you could see different results depending on what’s returned from the name resolution process. These results could be anything. The first time you run your application, you might get the address 10.1.2.3. The next time, you get a different address, 192.168.0.1. The third time, you could get 172.16.7.8, and so on.

In the server example, .listen() enables a server to accept connections. It makes the server a “listening” socket:

# echo-server.py

# ...

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

s.listen()

conn, addr = s.accept()

# ...The .listen() method has a backlog parameter. It specifies the number of unaccepted connections that the system will allow before refusing new connections. Starting in Python 3.5, it’s optional. If not specified, a default backlog value is chosen.

If your server receives a lot of connection requests simultaneously, increasing the backlog value may help by setting the maximum length of the queue for pending connections. The maximum value is system dependent. For example, on Linux, see /proc/sys/net/core/somaxconn.

The .accept() method blocks execution and waits for an incoming connection. When a client connects, it returns a new socket object representing the connection and a tuple holding the address of the client. The tuple will contain (host, port) for IPv4 connections or (host, port, flowinfo, scopeid) for IPv6. See Socket Address Families in the reference section for details on the tuple values.

One thing that’s imperative to understand is that you now have a new socket object from .accept(). This is important because it’s the socket that you’ll use to communicate with the client. It’s distinct from the listening socket that the server is using to accept new connections:

# echo-server.py

# ...

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

s.listen()

conn, addr = s.accept()

with conn:

print(f"Connected by {addr}")

while True:

data = conn.recv(1024)

if not data:

break

conn.sendall(data)After .accept() provides the client socket object conn, an infinite while loop is used to loop over blocking calls to conn.recv(). This reads whatever data the client sends and echoes it back using conn.sendall().

If conn.recv() returns an empty bytes object, b'', that signals that the client closed the connection and the loop is terminated. The with statement is used with conn to automatically close the socket at the end of the block.

Echo Client #

Now let’s look at the client:

# echo-client.py

import socket

HOST = "127.0.0.1" # The server's hostname or IP address

PORT = 65432 # The port used by the server

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.connect((HOST, PORT))

s.sendall(b"Hello, world")

data = s.recv(1024)

print(f"Received {data!r}")

In comparison to the server, the client is pretty simple. It creates a socket object, uses .connect() to connect to the server and calls s.sendall() to send its message. Lastly, it calls s.recv() to read the server’s reply and then prints it.

Running the Echo Client and Server #

In this section, you’ll run the client and server to see how they behave and inspect what’s happening.

Open a terminal or command prompt, navigate to the directory that contains your scripts, ensure that you have Python 3.6 or above installed and on your path, then run the server:

$ python echo-server.pyYour terminal will appear to hang. That’s because the server is blocked, or suspended, on .accept():

# echo-server.py

# ...

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.bind((HOST, PORT))

s.listen()

conn, addr = s.accept()

with conn:

print(f"Connected by {addr}")

while True:

data = conn.recv(1024)

if not data:

break

conn.sendall(data)It’s waiting for a client connection. Now, open another terminal window or command prompt and run the client:

$ python echo-client.py

Received b'Hello, world'In the server window, you should notice something like this:

$ python echo-server.py

Connected by ('127.0.0.1', 64623)In the output above, the server printed the addr tuple returned from s.accept(). This is the client’s IP address and TCP port number. The port number, 64623, will most likely be different when you run it on your machine.

Viewing Socket State #

To see the current state of sockets on your host, use netstat. It’s available by default on macOS, Linux, and Windows.

Here’s the netstat output from macOS after starting the server:

$ netstat -an

Active Internet connections (including servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address (state)

tcp4 0 0 127.0.0.1.65432 *.* LISTENNotice that Local Address is 127.0.0.1.65432. If echo-server.py had used HOST = "" instead of HOST = "127.0.0.1", netstat would show this:

$ netstat -an

Active Internet connections (including servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address (state)

tcp4 0 0 *.65432 *.* LISTENLocal Address is *.65432, which means all available host interfaces that support the address family will be used to accept incoming connections. In this example, socket.AF_INET was used (IPv4) in the call to socket(). You can see this in the Proto column: tcp4.

The output above is trimmed to show the echo server only. You’ll likely see much more output, depending on the system you’re running it on. The things to notice are the columns Proto, Local Address, and (state). In the last example above, netstat shows that the echo server is using an IPv4 TCP socket (tcp4), on port 65432 on all interfaces (*.65432), and it’s in the listening state (LISTEN).

Another way to access this, along with additional helpful information, is to use lsof (list open files). It’s available by default on macOS and can be installed on Linux using your package manager, if it’s not already:

$ lsof -i -n

COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME

Python 67982 nathan 3u IPv4 0xecf272 0t0 TCP *:65432 (LISTEN)lsof gives you the COMMAND, PID (process ID), and USER (user ID) of open Internet sockets when used with the -i option. Above is the echo server process.

netstat and lsof have a lot of options available and differ depending on the OS that you’re running them on. Check the man page or documentation for both. They’re definitely worth spending a little time with and getting to know. You’ll be rewarded. On macOS and Linux, use man netstat and man lsof. For Windows, use netstat /?.

Here’s a common error that you’ll encounter when a connection attempt is made to a port with no listening socket:

$ python echo-client.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "./echo-client.py", line 9, in <module>

s.connect((HOST, PORT))

ConnectionRefusedError: [Errno 61] Connection refusedEither the specified port number is wrong or the server isn’t running. Or maybe there’s a firewall in the path that’s blocking the connection, which can be easy to forget about. You may also see the error Connection timed out. Get a firewall rule added that allows the client to connect to the TCP port!

Communication Breakdown #

Now you’ll take a closer look at how the client and server communicated with each other:

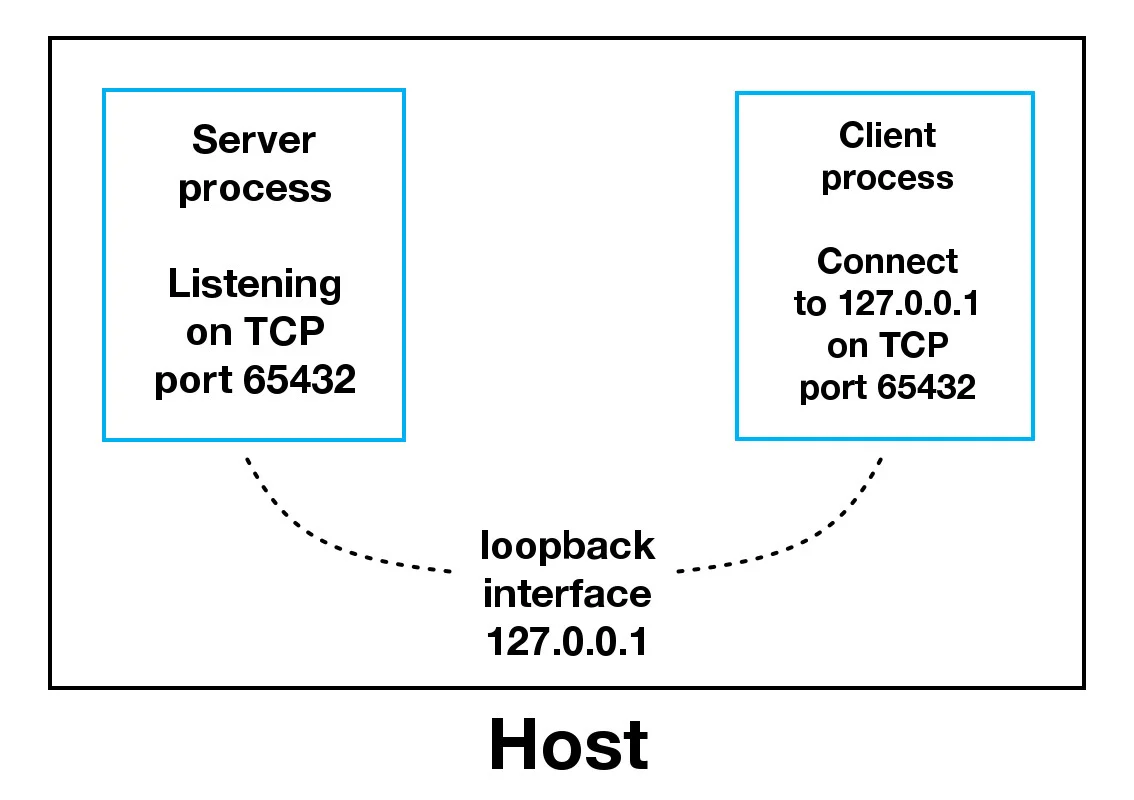

When using the loopback interface (IPv4 address 127.0.0.1 or IPv6 address ::1), data never leaves the host or touches the external network. In the diagram above, the loopback interface is contained inside the host. This represents the internal nature of the loopback interface and shows that connections and data that transit it are local to the host. This is why you’ll also hear the loopback interface and IP address 127.0.0.1 or ::1 referred to as “localhost.”

Applications use the loopback interface to communicate with other processes running on the host and for security and isolation from the external network. Because it’s internal and accessible only from within the host, it’s not exposed.

You can see this in action if you have an application server that uses its own private database. If it’s not a database used by other servers, it’s probably configured to listen for connections on the loopback interface only. If this is the case, other hosts on the network can’t connect to it.

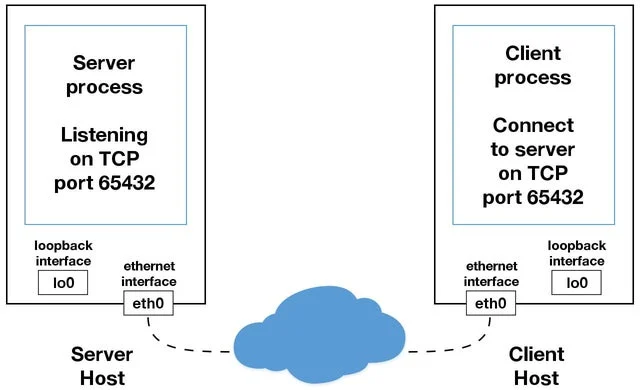

When you use an IP address other than 127.0.0.1 or ::1 in your applications, it’s probably bound to an Ethernet interface that’s connected to an external network. This is your gateway to other hosts outside of your “localhost” kingdom:

Be careful out there. It’s a nasty, cruel world. Be sure to read the section Using Hostnames before venturing from the safe confines of “localhost.” There’s a security note that applies even if you’re not using hostnames but are using IP addresses only.

Handling Multiple Connections #

The echo server definitely has its limitations. The biggest one is that it serves only one client and then exits. The echo client has this limitation too, but there’s an additional problem. When the client uses s.recv(), it’s possible that it will return only one byte, b'H' from b'Hello, world':

# echo-client.py

# ...

with socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) as s:

s.connect((HOST, PORT))

s.sendall(b"Hello, world")

data = s.recv(1024)

print(f"Received {data!r}")The bufsize argument of 1024 used above is the maximum amount of data to be received at once. It doesn’t mean that .recv() will return 1024 bytes.

The .send() method also behaves this way. It returns the number of bytes sent, which may be less than the size of the data passed in. You’re responsible for checking this and calling .send() as many times as needed to send all of the data:

“Applications are responsible for checking that all data has been sent; if only some of the data was transmitted, the application needs to attempt delivery of the remaining data.” (Source)

In the example above, you avoided having to do this by using .sendall():

“Unlike send(), this method continues to send data from bytes until either all data has been sent or an error occurs.

Noneis returned on success.” (Source)

You have two problems at this point:

- How do you handle multiple connections concurrently?

- You need to call

.send()and.recv()until all data is sent or received.

What can you do? There are many approaches to concurrency. A popular approach is to use Asynchronous I/O. asyncio was introduced into the standard library in Python 3.4. The traditional choice is to use threads.

The trouble with concurrency is it’s hard to get right. There are many subtleties to consider and guard against. All it takes is for one of these to manifest itself and your application may suddenly fail in not-so-subtle ways.

This isn’t meant to scare you away from learning and using concurrent programming. If your application needs to scale, it’s a necessity if you want to use more than one processor or one core. However, for this tutorial, you’ll use something that’s even more traditional than threads and easier to reason about. You’re going to use the granddaddy of system calls: .select().

The .select() method allows you to check for I/O completion on more than one socket. So you can call .select() to see which sockets have I/O ready for reading and/or writing. But this is Python, so there’s more. You’re going to use the selectors module in the standard library so that the most efficient implementation is used, regardless of the operating system you happen to be running on:

“This module allows high-level and efficient I/O multiplexing, built upon the select module primitives. Users are encouraged to use this module instead, unless they want precise control over the OS-level primitives used.” (Source)

Still, by using .select(), you’re not able to run concurrently. That said, depending on your workload, this approach may still be plenty fast. It depends on what your application needs to do when it services a request, and the number of clients it needs to support.

asyncio uses single-threaded cooperative multitasking and an event loop to manage tasks. With .select(), you’ll be writing your own version of an event loop, albeit more simply and synchronously. When using multiple threads, even though you have concurrency, you currently have to use the [GIL] (Global Interpreter Lock) with CPython and PyPy. This effectively limits the amount of work you can do in parallel anyway.

This is all to say that using .select() may be a perfectly fine choice. Don’t feel like you have to use asyncio, threads, or the latest asynchronous library. Typically, in a network application, your application is I/O bound anyway: it could be waiting on the local network, for endpoints on the other side of the network, for disk writes, and so forth.

If you’re getting requests from clients that initiate CPU bound work, look at the concurrent.futures module. It contains the class ProcessPoolExecutor, which uses a pool of processes to execute calls asynchronously.

If you use multiple processes, the operating system is able to schedule your Python code to run in parallel on multiple processors or cores, without the GIL. For ideas and inspiration, see the PyCon talk John Reese - Thinking Outside the GIL with AsyncIO and Multiprocessing - PyCon 2018.

In the next section, you’ll look at examples of a server and client that address these problems. They use .select() to handle multiple connections simultaneously and call .send() and .recv() as many times as needed.

Multi-Connection Client and Server #

In the next two sections, you’ll create a server and client that handles multiple connections using a selector object created from the selectors module.

Multi-Connection Server #

First, turn your attention to the multi-connection server. The first part sets up the listening socket:

# multiconn-server.py

import sys

import socket

import selectors

import types

sel = selectors.DefaultSelector()

# ...

host, port = sys.argv[1], int(sys.argv[2])

lsock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

lsock.bind((host, port))

lsock.listen()

print(f"Listening on {(host, port)}")

lsock.setblocking(False)

sel.register(lsock, selectors.EVENT_READ, data=None)The biggest difference between this server and the echo server is the call to lsock.setblocking(False) to configure the socket in non-blocking mode. Calls made to this socket will no longer block. When it’s used with sel.select(), as you’ll see below, you can wait for events on one or more sockets and then read and write data when it’s ready.

sel.register() registers the socket to be monitored with sel.select() for the events that you’re interested in. For the listening socket, you want read events: selectors.EVENT_READ.

To store whatever arbitrary data you’d like along with the socket, you’ll use data. It’s returned when .select() returns. You’ll use data to keep track of what’s been sent and received on the socket.

Next is the event loop:

# multiconn-server.py

# ...

try:

while True:

events = sel.select(timeout=None)

for key, mask in events:

if key.data is None:

accept_wrapper(key.fileobj)

else:

service_connection(key, mask)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("Caught keyboard interrupt, exiting")

finally:

sel.close()sel.select(timeout=None) blocks until there are sockets ready for I/O. It returns a list of tuples, one for each socket. Each tuple contains a key and a mask. The key is a SelectorKey [namedtuple] that contains a fileobj attribute. key.fileobj is the socket object, and mask is an event mask of the operations that are ready.

If key.data is None, then you know it’s from the listening socket and you need to accept the connection. You’ll call your own accept_wrapper() function to get the new socket object and register it with the selector. You’ll look at that in a moment.

If key.data is not None, then you know it’s a client socket that’s already been accepted, and you need to service it. service_connection() is then called with key and mask as arguments, and that’s everything you need to operate on the socket.

Here’s what your accept_wrapper() function does:

# multiconn-server.py

# ...

def accept_wrapper(sock):

conn, addr = sock.accept() # Should be ready to read

print(f"Accepted connection from {addr}")

conn.setblocking(False)

data = types.SimpleNamespace(addr=addr, inb=b"", outb=b"")

events = selectors.EVENT_READ | selectors.EVENT_WRITE

sel.register(conn, events, data=data)

# ...Because the listening socket was registered for the event selectors.EVENT_READ, it should be ready to read. You call sock.accept() and then call conn.setblocking(False) to put the socket in non-blocking mode.

Remember, this is the main objective in this version of the server because you don’t want it to block. If it blocks, then the entire server is stalled until it returns. That means other sockets are left waiting even though the server isn’t actively working. This is the dreaded “hang” state that you don’t want your server to be in.

Next, you create an object to hold the data that you want included along with the socket using a SimpleNamespace. Because you want to know when the client connection is ready for reading and writing, both of those events are set with the [bitwise OR] operator:

# multiconn-server.py

# ...

def accept_wrapper(sock):

conn, addr = sock.accept() # Should be ready to read

print(f"Accepted connection from {addr}")

conn.setblocking(False)

data = types.SimpleNamespace(addr=addr, inb=b"", outb=b"")

events = selectors.EVENT_READ | selectors.EVENT_WRITE

sel.register(conn, events, data=data)

# ...The events mask, socket, and data objects are then passed to sel.register().

Now take a look at service_connection() to see how a client connection is handled when it’s ready:

# multiconn-server.py

# ...

def service_connection(key, mask):

sock = key.fileobj

data = key.data

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

recv_data = sock.recv(1024) # Should be ready to read

if recv_data:

data.outb += recv_data

else:

print(f"Closing connection to {data.addr}")

sel.unregister(sock)

sock.close()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

if data.outb:

print(f"Echoing {data.outb!r} to {data.addr}")

sent = sock.send(data.outb) # Should be ready to write

data.outb = data.outb[sent:]

# ...This is the heart of the simple multi-connection server. key is the namedtuple returned from .select() that contains the socket object (fileobj) and data object. mask contains the events that are ready.

If the socket is ready for reading, then mask & selectors.EVENT_READ will evaluate to True, so sock.recv() is called. Any data that’s read is appended to data.outb so that it can be sent later.

Note the else: block to check if no data is received:

# multiconn-server.py

# ...

def service_connection(key, mask):

sock = key.fileobj

data = key.data

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

recv_data = sock.recv(1024) # Should be ready to read

if recv_data:

data.outb += recv_data

else:

print(f"Closing connection to {data.addr}")

sel.unregister(sock)

sock.close()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

if data.outb:

print(f"Echoing {data.outb!r} to {data.addr}")

sent = sock.send(data.outb) # Should be ready to write

data.outb = data.outb[sent:]

# ...If no data is received, this means that the client has closed their socket, so the server should too. But don’t forget to call sel.unregister() before closing, so it’s no longer monitored by .select().

When the socket is ready for writing, which should always be the case for a healthy socket, any received data stored in data.outb is echoed to the client using sock.send(). The bytes sent are then removed from the send buffer:

# multiconn-server.py

# ...

def service_connection(key, mask):

# ...

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

if data.outb:

print(f"Echoing {data.outb!r} to {data.addr}")

sent = sock.send(data.outb) # Should be ready to write

data.outb = data.outb[sent:]

# ...The .send() method returns the number of bytes sent. This number can then be used with [slice notation] on the .outb buffer to discard the bytes sent.

Multi-Connection Client #

Now take a look at the multi-connection client, multiconn-client.py. It’s very similar to the server, but instead of listening for connections, it starts by initiating connections via start_connections():

# multiconn-client.py

import sys

import socket

import selectors

import types

sel = selectors.DefaultSelector()

messages = [b"Message 1 from client.", b"Message 2 from client."]

def start_connections(host, port, num_conns):

server_addr = (host, port)

for i in range(0, num_conns):

connid = i + 1

print(f"Starting connection {connid} to {server_addr}")

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

sock.setblocking(False)

sock.connect_ex(server_addr)

events = selectors.EVENT_READ | selectors.EVENT_WRITE

data = types.SimpleNamespace(

connid=connid,

msg_total=sum(len(m) for m in messages),

recv_total=0,

messages=messages.copy(),

outb=b"",

)

sel.register(sock, events, data=data)

# ...num_conns is read from the command-line and is the number of connections to create to the server. Just like the server, each socket is set to non-blocking mode.

You use .connect_ex() instead of .connect() because .connect() would immediately raise a BlockingIOError exception. The .connect_ex() method initially returns an error indicator, errno.EINPROGRESS, instead of raising an exception that would interfere with the connection in progress. Once the connection is completed, the socket is ready for reading and writing and is returned by .select().

After the socket is set up, the data you want to store with the socket is created using SimpleNamespace. The messages that the client will send to the server are copied using messages.copy() because each connection will call socket.send() and modify the list. Everything needed to keep track of what the client needs to send, has sent, and has received, including the total number of bytes in the messages, is stored in the object data.

Check out the changes made from the server’s service_connection() for the client’s version:

def service_connection(key, mask):

sock = key.fileobj

data = key.data

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

recv_data = sock.recv(1024) # Should be ready to read

if recv_data:

- data.outb += recv_data

+ print(f"Received {recv_data!r} from connection {data.connid}")

+ data.recv_total += len(recv_data)

- else:

- print(f"Closing connection {data.connid}")

+ if not recv_data or data.recv_total == data.msg_total:

+ print(f"Closing connection {data.connid}")

sel.unregister(sock)

sock.close()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

+ if not data.outb and data.messages:

+ data.outb = data.messages.pop(0)

if data.outb:

- print(f"Echoing {data.outb!r} to {data.addr}")

+ print(f"Sending {data.outb!r} to connection {data.connid}")

sent = sock.send(data.outb) # Should be ready to write

data.outb = data.outb[sent:]It’s fundamentally the same but for one important difference. The client keeps track of the number of bytes it’s received from the server so that it can close its side of the connection. When the server detects this, it closes its side of the connection too.

Note that by doing this, the server depends on the client being well-behaved: the server expects the client to close its side of the connection when it’s done sending messages. If the client doesn’t close, the server will leave the connection open. In a real application, you may want to guard against this in your server by implementing a timeout to prevent client connections from accumulating if they don’t send a request after a certain amount of time.

Running the Multi-Connection Client and Server #

Now it’s time to run multiconn-server.py and multiconn-client.py. They both use command-line arguments. You can run them without arguments to see the options.

For the server, pass host and port numbers:

$ python multiconn-server.py

Usage: multiconn-server.py <host> <port>For the client, also pass the number of connections to create to the server, num_connections:

$ python multiconn-client.py

Usage: multiconn-client.py <host> <port> <num_connections>Below is the server output when listening on the loopback interface on port 65432:

$ python multiconn-server.py 127.0.0.1 65432

Listening on ('127.0.0.1', 65432)

Accepted connection from ('127.0.0.1', 61354)

Accepted connection from ('127.0.0.1', 61355)

Echoing b'Message 1 from client.Message 2 from client.' to ('127.0.0.1', 61354)

Echoing b'Message 1 from client.Message 2 from client.' to ('127.0.0.1', 61355)

Closing connection to ('127.0.0.1', 61354)

Closing connection to ('127.0.0.1', 61355)Below is the client output when it creates two connections to the server above:

$ python multiconn-client.py 127.0.0.1 65432 2

Starting connection 1 to ('127.0.0.1', 65432)

Starting connection 2 to ('127.0.0.1', 65432)

Sending b'Message 1 from client.' to connection 1

Sending b'Message 2 from client.' to connection 1

Sending b'Message 1 from client.' to connection 2

Sending b'Message 2 from client.' to connection 2

Received b'Message 1 from client.Message 2 from client.' from connection 1

Closing connection 1

Received b'Message 1 from client.Message 2 from client.' from connection 2

Closing connection 2Great! Now you’ve run the multi-connection client and server. In the next section, you’ll take this example even further.

Application Client and Server #

The multi-connection client and server example is definitely an improvement compared with where you started. However, now you can take one more step and address the shortcomings of the previous multiconn example in a final implementation: the application client and server.

You want a client and server that handle errors appropriately so that other connections aren’t affected. Obviously, your client or server shouldn’t come crashing down in a ball of fury if an exception isn’t caught. This is something you haven’t had to worry about until now, because the examples have intentionally left out error handling for brevity and clarity.

Now that you’re familiar with the basic API, non-blocking sockets, and .select(), you can add some error handling and address the elephant in the room, which the examples have kept hidden from you behind that large curtain over there. Remember that custom class that was mentioned way back in the introduction? That’s what you’re going to explore next.

First, you’ll address the errors:

“All errors raise exceptions. The normal exceptions for invalid argument types and out-of-memory conditions can be raised; starting from Python 3.3, errors related to socket or address semantics raise

OSErroror one of its subclasses.” (Source)

So, one thing you need to do is catch OSError. Another important consideration in relation to errors is timeouts. You’ll see them discussed in many places in the documentation. Timeouts happen and are a so-called normal error. Hosts and routers are rebooted, switch ports go bad, cables go bad, cables get unplugged, you name it. You should be prepared for these and other errors, handling them in your code.

What about the elephant in the room? As hinted by the socket type socket.SOCK_STREAM, when using TCP, you’re reading from a continuous stream of bytes. It’s like reading from a file on disk, but instead you’re reading bytes from the network. However, unlike reading a file, there’s no f.seek().

In other words, you can’t reposition the socket pointer, if there was one, and move around the data.

When bytes arrive at your socket, there are network buffers involved. Once you’ve read them, they need to be saved somewhere, or else you will have dropped them. Calling .recv() again reads the next stream of bytes available from the socket.

You’ll be reading from the socket in chunks. So, you need to call .recv() and save the data in a buffer until you’ve read enough bytes to have a complete message that makes sense to your application.

It’s up to you to define and keep track of where the message boundaries are. As far as the TCP socket is concerned, it’s just sending and receiving raw bytes to and from the network. It knows nothing about what those raw bytes mean.

This is why you need to define an application-layer protocol. What’s an application-layer protocol? Put simply, your application will send and receive messages. The format of these messages are your application’s protocol.

In other words, the length and format that you choose for these messages define the semantics and behavior of your application. This is directly related to what you learned in the previous paragraph regarding reading bytes from the socket. When you’re reading bytes with .recv(), you need to keep up with how many bytes were read, and figure out where the message boundaries are.

How can you do this? One way is to always send fixed-length messages. If they’re always the same size, then it’s easy. When you’ve read that number of bytes into a buffer, then you know you have one complete message.

However, using fixed-length messages is inefficient for small messages where you’d need to use padding to fill them out. Also, you’re still left with the problem of what to do about data that doesn’t fit into one message.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn a generic approach, one that’s used by many protocols, including HTTP. You’ll prefix messages with a header that includes the content length as well as any other fields you need. By doing this, you’ll only need to keep up with the header. Once you’ve read the header, you can process it to determine the length of the message’s content. With the content length, you can then read that number of bytes to consume it.

You’ll implement this by creating a custom class that can send and receive messages that contain text or binary data. You can improve and extend this class for your own applications. The most important thing is that you’ll be able to see an example of how this is done.

Before you get started, there’s something you need to know regarding sockets and bytes. As you learned earlier, when sending and receiving data via sockets, you’re sending and receiving raw bytes.

If you receive data and want to use it in a context where it’s interpreted as multiple bytes, for example a 4-byte integer, you’ll need to take into account that it could be in a format that’s not native to your machine’s CPU. The client or server on the other end could have a CPU that uses a different byte order than your own. If this is the case, then you’ll need to convert it to your host’s native byte order before using it.

This byte order is referred to as a CPU’s endianness. See Byte Endianness in the reference section for details. You’ll avoid this issue by taking advantage of [Unicode] for your message header and using the encoding UTF-8. Since UTF-8 uses an 8-bit encoding, there are no byte ordering issues.

You can find an explanation in Python’s Encodings and Unicode documentation. Note that this applies to the text header only. You’ll use an explicit type and encoding defined in the header for the content that’s being sent, the message payload. This will allow you to transfer any data that you’d like (text or binary), in any format.

You can easily determine the byte order of your machine by using sys.byteorder. For example, you could see something like this:

$ python -c 'import sys; print(repr(sys.byteorder))'

'little'If you run this in a virtual machine that emulates a big-endian CPU (PowerPC), then something like this happens:

$ python -c 'import sys; print(repr(sys.byteorder))'

'big'In this example application, your application-layer protocol defines the header as Unicode text with a UTF-8 encoding. For the actual content in the message, the message payload, you’ll still have to swap the byte order manually if needed.

This will depend on your application and whether or not it needs to process multi-byte binary data from a machine with a different endianness. You can help your client or server implement binary support by adding additional headers and using them to pass parameters, similar to HTTP.

Don’t worry if this doesn’t make sense yet. In the next section, you’ll see how all of this works and fits together.

Application Protocol Header #

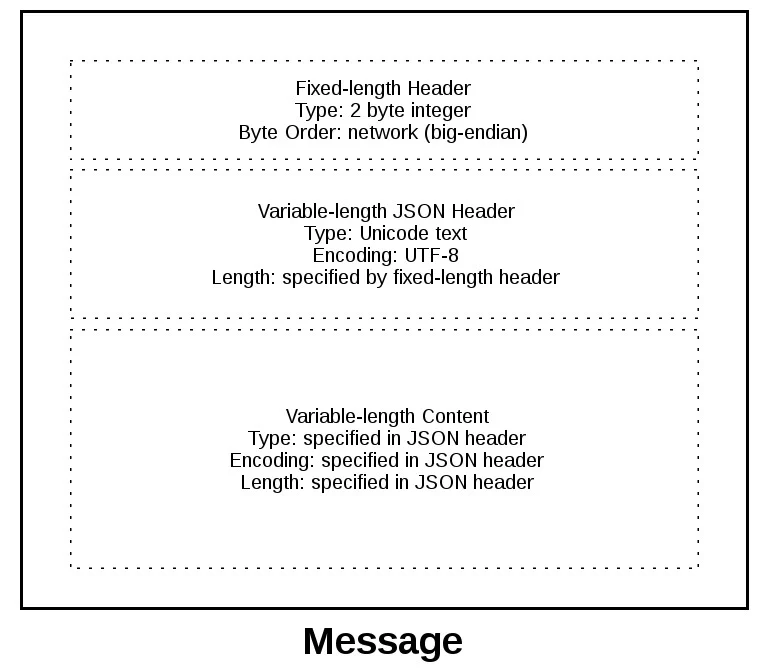

Now you’ll fully define the protocol header. The protocol header is:

- Variable-length text

- Unicode with the encoding UTF-8

- A Python dictionary serialized using JSON

The required headers, or sub-headers, in the protocol header’s dictionary are as follows:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

byteorder | The byte order of the machine (uses sys.byteorder). This may not be required for your application. |

content-length | The length of the content in bytes. |

content-type | The type of content in the payload, for example, text/json or binary/my-binary-type. |

content-encoding | The encoding used by the content, for example, utf-8 for Unicode text or binary for binary data. |

These headers inform the receiver about the content in the payload of the message. This allows you to send arbitrary data while providing enough information so that the content can be decoded and interpreted correctly by the receiver. Because the headers are in a dictionary, it’s easy to add additional headers by inserting key-value pairs as needed.

Sending an Application Message #

There’s still a bit of a problem. You have a variable-length header, which is nice and flexible, but how do you know the length of the header when reading it with .recv()?

When you previously learned about using .recv() and message boundaries, you also learned that fixed-length headers can be inefficient. That’s true, but you’re going to use a small, 2-byte, fixed-length header to prefix the JSON header that contains its length.

You can think of this as a hybrid approach to sending messages. In effect, you’re bootstrapping the message receive process by sending the length of the header first. This makes it easy for your receiver to deconstruct the message.

To give you a better idea of the message format, check out a message in its entirety:

A message starts with a fixed-length header of two bytes, which is an integer in network byte order. This is the length of the next header, the variable-length JSON header. Once you’ve read two bytes with .recv(), then you know you can process the two bytes as an integer and then read that number of bytes before decoding the UTF-8 JSON header.

The JSON header contains a dictionary of additional headers. One of those is content-length, which is the number of bytes of the message’s content (not including the JSON header). Once you’ve called .recv() and read content-length bytes, then you’ve reached a message boundary, meaning you’ve read an entire message.

Application Message Class #

Finally, the payoff! In this section, you’ll study the Message class and see how it’s used with .select() when read and write events happen on the socket.

This example application reflects what types of messages a client and server could reasonably use. You’re far beyond toy echo clients and servers at this point!

To keep things simple and still demonstrate how things would work in a real application, this example uses an application protocol that implements a basic search feature. The client sends a search request and the server does a lookup for a match. If the request sent by the client isn’t recognized as a search, the server assumes it’s a binary request and returns a binary response.

After reading the following sections, running the examples, and experimenting with the code, you’ll see how things work. You can then use the Message class as a starting point and modify it for your own use.

The application is not that far off from the multiconn client and server example. The event loop code stays the same in app-client.py and app-server.py. What you’re going to do is move the message code into a class named Message and add methods to support reading, writing, and processing of the headers and content. This is a great example for using a [class].

As you learned before and you’ll see below, working with sockets involves keeping state. By using a class, you keep all of the state, data, and code bundled together in an organized unit. An instance of the class is created for each socket in the client and server when a connection is started or accepted.

The class is mostly the same for both the client and the server for the wrapper and utility methods. They start with an underscore, like Message._json_encode(). These methods simplify working with the class. They help other methods by allowing them to stay shorter and support the DRY principle.

The server’s Message class works in essentially the same way as the client’s and vice-versa. The difference is that the client initiates the connection and sends a request message, followed by processing the server’s response message. Conversely, the server waits for a connection, processes the client’s request message, and then sends a response message.

It looks like this:

| Step | Endpoint | Action / Message Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Client | Sends a Message containing request content |

| 2 | Server | Receives and processes client request Message |

| 3 | Server | Sends a Message containing response content |

| 4 | Client | Receives and processes server response Message |

Here’s the file and code layout:

| Application | File | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Server | app-server.py | The server’s main script |

| Server | libserver.py | The server’s Message class |

| Client | app-client.py | The client’s main script |

| Client | libclient.py | The client’s Message class |

Message Entry Point #

Understanding how the Message class works can be a challenge because there’s an aspect of its design that might not be immediately obvious. Why? Managing state.

After a Message object is created, it’s associated with a socket that’s monitored for events using selector.register():

# app-server.py

# ...

def accept_wrapper(sock):

conn, addr = sock.accept() # Should be ready to read

print(f"Accepted connection from {addr}")

conn.setblocking(False)

message = libserver.Message(sel, conn, addr)

sel.register(conn, selectors.EVENT_READ, data=message)

# ...When events are ready on the socket, they’re returned by selector.select(). You can then get a reference back to the message object using the data attribute on the key object and call a method in Message:

# app-server.py

# ...

try:

while True:

events = sel.select(timeout=None)

for key, mask in events:

if key.data is None:

accept_wrapper(key.fileobj)

else:

message = key.data

try:

message.process_events(mask)

# ...

# ...Looking at the event loop above, you’ll see that sel.select() is in the driver’s seat. It’s blocking, waiting at the top of the loop for events. It’s responsible for waking up when read and write events are ready to be processed on the socket. Which means, indirectly, it’s also responsible for calling the method .process_events(). That’s why .process_events() is the entry point.

Here’s what the .process_events() method does:

# libserver.py

# ...

class Message:

def __init__(self, selector, sock, addr):

# ...

# ...

def process_events(self, mask):

if mask & selectors.EVENT_READ:

self.read()

if mask & selectors.EVENT_WRITE:

self.write()

# ...That’s good: .process_events() is simple. It can only do two things: call .read() and .write().

This is where managing state comes in. If another method depended on state variables having a certain value, then they would only be called from .read() and .write(). This keeps the logic as simple as possible as events come in on the socket for processing.

You might be tempted to use a mix of some methods that check the current state variables and, depending on their value, call other methods to process data outside .read() or .write(). In the end, this would likely prove too complex to manage and keep up with.

You should definitely modify the class to suit your own needs so that it works best for you, but you’ll probably have the best results if you keep the state checks and the calls to methods that depend on that state to the .read() and .write() methods if possible.

Now look at .read(). This is the server’s version, but the client’s is the same. It just uses a different method name, .process_response() instead of .process_request():

# libserver.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def read(self):

self._read()

if self._jsonheader_len is None:

self.process_protoheader()

if self._jsonheader_len is not None:

if self.jsonheader is None:

self.process_jsonheader()

if self.jsonheader:

if self.request is None:

self.process_request()

# ...The ._read() method is called first. It calls socket.recv() to read data from the socket and store it in a receive buffer.

Remember that when socket.recv() is called, all of the data that makes up a complete message may not have arrived yet. socket.recv() may need to be called again. This is why there are state checks for each part of the message before the appropriate method to process it is called.

Before a method processes its part of the message, it first checks to make sure enough bytes have been read into the receive buffer. If they have, it processes its respective bytes, removes them from the buffer and writes its output to a variable that’s used by the next processing stage. Because there are three components to a message, there are three state checks and process method calls:

| Message Component | Method | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed-length header | process_protoheader() | self._jsonheader_len |

| JSON header | process_jsonheader() | self.jsonheader |

| Content | process_request() | self.request |

Next, check out .write(). This is the server’s version:

# libserver.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def write(self):

if self.request:

if not self.response_created:

self.create_response()

self._write()

# ...The .write() method checks first for a request. If one exists and a response hasn’t been created, .create_response() is called. The .create_response() method sets the state variable response_created and writes the response to the send buffer.

The ._write() method calls socket.send() if there’s data in the send buffer.

Remember that when socket.send() is called, all of the data in the send buffer may not have been queued for transmission. The network buffers for the socket may be full, and socket.send() may need to be called again. This is why there are state checks. The .create_response() method should only be called once, but it’s expected that ._write() will need to be called multiple times.

The client version of .write() is similar:

# libclient.py

# ...

class Message:

def __init__(self, selector, sock, addr, request):

# ...

def write(self):

if not self._request_queued:

self.queue_request()

self._write()

if self._request_queued:

if not self._send_buffer:

# Set selector to listen for read events, we're done writing.

self._set_selector_events_mask("r")

# ...Because the client initiates a connection to the server and sends a request first, the state variable _request_queued is checked. If a request hasn’t been queued, it calls .queue_request(). The queue_request() method creates the request and writes it to the send buffer. It also sets the state variable _request_queued so that it’s only called once.

Just like for the server, ._write() calls socket.send() if there’s data in the send buffer.

The notable difference in the client’s version of .write() is the last check to see if the request has been queued. This will be explained more in the section Client Main Script, but the reason for this is to tell selector.select() to stop monitoring the socket for write events. If the request has been queued and the send buffer is empty, then you’re done writing and you’re only interested in read events. There’s no reason to be notified that the socket is writable.

To wrap up this section, consider this thought: the main purpose of this section was to explain that selector.select() is calling into the Message class via the method .process_events() and to describe how state is managed.

This is important because .process_events() will be called many times over the life of the connection. Therefore, make sure that any methods that should only be called once are either checking a state variable themselves, or the state variable set by the method is checked by the caller.

Server Main Script #

In the server’s main script app-server.py, arguments are read from the command line that specify the interface and port to listen on:

$ python app-server.py

Usage: app-server.py <host> <port>For example, to listen on the loopback interface on port 65432, enter:

$ python app-server.py 127.0.0.1 65432

Listening on ('127.0.0.1', 65432)Use an empty string for <host> to listen on all interfaces.

After creating the socket, a call is made to socket.setsockopt() with the option socket.SO_REUSEADDR:

# app-server.py

# ...

host, port = sys.argv[1], int(sys.argv[2])

lsock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

# Avoid bind() exception: OSError: [Errno 48] Address already in use

lsock.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

lsock.bind((host, port))

lsock.listen()

print(f"Listening on {(host, port)}")

lsock.setblocking(False)

sel.register(lsock, selectors.EVENT_READ, data=None)

# ...Setting this socket option avoids the error Address already in use. You’ll see this when starting the server on a port that has connections in the TIME_WAIT state.

For example, if the server actively closed a connection, it’ll remain in the TIME_WAIT state for two minutes or more, depending on the operating system. If you try to start the server again before the TIME_WAIT state expires, then you’ll get an OSError exception of Address already in use. This is a safeguard to make sure that any delayed packets in the network aren’t delivered to the wrong application.

The event loop catches any errors so that the server can stay up and continue to run:

# app-server.py

# ...

try:

while True:

events = sel.select(timeout=None)

for key, mask in events:

if key.data is None:

accept_wrapper(key.fileobj)

else:

message = key.data

try:

message.process_events(mask)

except Exception:

print(

f"Main: Error: Exception for {message.addr}:\n"

f"{traceback.format_exc()}"

)

message.close()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("Caught keyboard interrupt, exiting")

finally:

sel.close()When a client connection is accepted, a Message object is created:

# app-server.py

# ...

def accept_wrapper(sock):

conn, addr = sock.accept() # Should be ready to read

print(f"Accepted connection from {addr}")

conn.setblocking(False)

message = libserver.Message(sel, conn, addr)

sel.register(conn, selectors.EVENT_READ, data=message)

# ...The Message object is associated with the socket in the call to sel.register() and is initially set to be monitored for read events only. Once the request has been read, you’ll modify it to listen for write events only.

An advantage of taking this approach in the server is that in most cases, when a socket is healthy and there are no network issues, it’ll always be writable.

If you told sel.register() to also monitor EVENT_WRITE, then the event loop would immediately wake up and notify you that this is the case. However, at this point, there’s no reason to wake up and call .send() on the socket. There’s no response to send, because a request hasn’t been processed yet. This would consume and waste valuable CPU cycles.

Server Message Class #

In the section Message Entry Point, you learned how the Message object was called into action when socket events were ready via .process_events(). Now you’ll learn what happens as data is read on the socket and a component, or piece, of the message is ready to be processed by the server.

The server’s message class is in libserver.py, which is part of the source code you downloaded earlier. You can also download the code by clicking the link below:

The methods appear in the class in the order in which processing takes place for a message.

When the server has read at least two bytes, the fixed-length header can be processed:

# libserver.py

# ...

class Message:

def __init__(self, selector, sock, addr):

# ...

# ...

def process_protoheader(self):

hdrlen = 2

if len(self._recv_buffer) >= hdrlen:

self._jsonheader_len = struct.unpack(

">H", self._recv_buffer[:hdrlen]

)[0]

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[hdrlen:]

# ...The fixed-length header is a 2-byte integer in network, or big-endian, byte order. It contains the length of the JSON header. You’ll use struct.unpack() to read the value, decode it, and store it in self._jsonheader_len. After processing the piece of the message it’s responsible for, .process_protoheader() removes it from the receive buffer.

Just like with the fixed-length header, when there’s enough data in the receive buffer to contain the JSON header, it can be processed as well:

# libserver.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def process_jsonheader(self):

hdrlen = self._jsonheader_len

if len(self._recv_buffer) >= hdrlen:

self.jsonheader = self._json_decode(

self._recv_buffer[:hdrlen], "utf-8"

)

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[hdrlen:]

for reqhdr in (

"byteorder",

"content-length",

"content-type",

"content-encoding",

):

if reqhdr not in self.jsonheader:

raise ValueError(f"Missing required header '{reqhdr}'.")

# ...The method self._json_decode() is called to decode and deserialize the JSON header into a dictionary. Because the JSON header is defined as Unicode with a UTF-8 encoding, utf-8 is hardcoded in the call. The result is saved to self.jsonheader. After processing the piece of the message that it’s responsible for, process_jsonheader() removes it from the receive buffer.

Next is the actual content, or payload, of the message. It’s described by the JSON header in self.jsonheader. When content-length bytes are available in the receive buffer, the request can be processed:

# libserver.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def process_request(self):

content_len = self.jsonheader["content-length"]

if not len(self._recv_buffer) >= content_len:

return

data = self._recv_buffer[:content_len]

self._recv_buffer = self._recv_buffer[content_len:]

if self.jsonheader["content-type"] == "text/json":

encoding = self.jsonheader["content-encoding"]

self.request = self._json_decode(data, encoding)

print(f"Received request {self.request!r} from {self.addr}")

else:

# Binary or unknown content-type

self.request = data

print(

f"Received {self.jsonheader['content-type']} "

f"request from {self.addr}"

)

# Set selector to listen for write events, we're done reading.

self._set_selector_events_mask("w")

# ...After saving the message content to the data variable, .process_request() removes it from the receive buffer. Then, if the content type is JSON, .process_request() decodes and deserializes it. If it’s not, this example application assumes that it’s a binary request and simply prints the content type.

The last thing .process_request() does is modify the selector to monitor write events only. In the server’s main script, app-server.py, the socket is initially set to monitor read events only. Now that the request has been fully processed, you’re no longer interested in reading.

A response can now be created and written to the socket. When the socket is writable, .create_response() is called from .write():

# libserver.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def create_response(self):

if self.jsonheader["content-type"] == "text/json":

response = self._create_response_json_content()

else:

# Binary or unknown content-type

response = self._create_response_binary_content()

message = self._create_message(**response)

self.response_created = True

self._send_buffer += messageA response is created by calling other methods, depending on the content type. In this example application, a simple dictionary lookup is done for JSON requests when action == 'search'. For your own applications, you can define other methods that get called here.

After creating the response message, the state variable self.response_created is set so that .write() doesn’t call .create_response() again. Finally, the response is appended to the send buffer. This is seen by and sent via ._write().

One tricky bit to figure out is how to close the connection after the response is written. You can put the call to .close() in the method ._write():

# libserver.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def _write(self):

if self._send_buffer:

print(f"Sending {self._send_buffer!r} to {self.addr}")

try:

# Should be ready to write

sent = self.sock.send(self._send_buffer)

except BlockingIOError:

# Resource temporarily unavailable (errno EWOULDBLOCK)

pass

else:

self._send_buffer = self._send_buffer[sent:]

# Close when the buffer is drained. The response has been sent.

if sent and not self._send_buffer:

self.close()

# ...Although it’s somewhat hidden, this is an acceptable trade-off given that the Message class only handles one message per connection. After the response is written, there’s nothing left for the server to do. It’s completed its work.

Client Main Script #

In the section [Message Entry Point], you learned how the message object was called into action when socket events were ready via .process_events(). Now you’ll learn what happens after data is read and written on the socket and a message is ready to be processed by the client.

The client’s message class is in libclient.py, which is part of the source code you downloaded earlier. You can also download the code by clicking the link below:

The methods appear in the class in the order in which processing takes place for a message.

The first task for the client is to queue the request:

# libclient.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def queue_request(self):

content = self.request["content"]

content_type = self.request["type"]

content_encoding = self.request["encoding"]

if content_type == "text/json":

req = {

"content_bytes": self._json_encode(content, content_encoding),

"content_type": content_type,

"content_encoding": content_encoding,

}

else:

req = {

"content_bytes": content,

"content_type": content_type,

"content_encoding": content_encoding,

}

message = self._create_message(**req)

self._send_buffer += message

self._request_queued = True

# ...The dictionaries used to create the request, depending on what was passed on the command line, are in the client’s main script, app-client.py. The request dictionary is passed as an argument to the class when a Message object is created.

The request message is created and appended to the send buffer, which is then seen by and sent via ._write(). The state variable self._request_queued is set so that .queue_request() isn’t called again.

After the request has been sent, the client waits for a response from the server.

The methods for reading and processing a message in the client are the same as for the server. As response data is read from the socket, the process header methods are called: .process_protoheader() and .process_jsonheader().

The difference is in the naming of the final process methods and the fact that they’re processing a response, not creating one: .process_response(), ._process_response_json_content(), and ._process_response_binary_content().

Last, but certainly not least, is the final call for .process_response():

# libclient.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def process_response(self):

# ...

# Close when response has been processed

self.close()

# ...Message Class Wrapup #

To conclude your learning about the Message class, it’s worth mentioning a couple of things that are important to notice with a few of the supporting methods.

Any exceptions raised by the class are caught by the main script in the except clause inside the event loop:

# app-client.py

# ...

try:

while True:

events = sel.select(timeout=1)

for key, mask in events:

message = key.data

try:

message.process_events(mask)

except Exception:

print(

f"Main: Error: Exception for {message.addr}:\n"

f"{traceback.format_exc()}"

)

message.close()

# Check for a socket being monitored to continue.

if not sel.get_map():

break

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("Caught keyboard interrupt, exiting")

finally:

sel.close()Note the line: message.close().

This is a really important line, for more than one reason! Not only does it make sure that the socket is closed, but message.close() also removes the socket from being monitored by .select(). This greatly simplifies the code in the class and reduces complexity. If there’s an exception or you explicitly raise one yourself, you know .close() will take care of the cleanup.

The methods Message._read() and Message._write() also contain something interesting:

# libclient.py

# ...

class Message:

# ...

def _read(self):

try:

# Should be ready to read

data = self.sock.recv(4096)

except BlockingIOError:

# Resource temporarily unavailable (errno EWOULDBLOCK)

pass

else:

if data:

self._recv_buffer += data

else:

raise RuntimeError("Peer closed.")

# ...Note the except BlockingIOError: line.

The ._write() method has one too. These lines are important because they catch a temporary error and skip over it using pass. The temporary error is when the socket would block, for example if it’s waiting on the network or the other end of the connection, also known as its peer.

By catching and skipping over the exception with pass, .select() will eventually trigger a new call, and you’ll get another chance to read or write the data.

Running the Application Client and Server #

After all of this hard work, it’s time to have some fun and run some searches!

In these examples, you’ll run the server so that it listens on all interfaces by passing an empty string for the host argument. This will allow you to run the client and connect from a virtual machine that’s on another network. It emulates a big-endian PowerPC machine.

First, start the server:

$ python app-server.py '' 65432

Listening on ('', 65432)Now run the client and enter a search. See if you can find him:

$ python app-client.py 10.0.1.1 65432 search morpheus

Starting connection to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Sending b'\x00d{"byteorder": "big", "content-type": "text/json", "content-encoding": "utf-8", "content-length": 41}{"action": "search", "value": "morpheus"}' to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Received response {'result': 'Follow the white rabbit. 🐰'} from ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Got result: Follow the white rabbit. 🐰

Closing connection to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)You might notice that the terminal is running a shell that’s using a text encoding of Unicode (UTF-8), so the output above prints nicely with emojis.

Now see if you can find the puppies:

$ python app-client.py 10.0.1.1 65432 search 🐶

Starting connection to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Sending b'\x00d{"byteorder": "big", "content-type": "text/json", "content-encoding": "utf-8", "content-length": 37}{"action": "search", "value": "\xf0\x9f\x90\xb6"}' to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Received response {'result': '🐾 Playing ball! 🏐'} from ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Got result: 🐾 Playing ball! 🏐

Closing connection to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)Notice the byte string sent over the network for the request in the sending line. It’s easier to see if you look for the bytes printed in hex that represent the puppy emoji: \xf0\x9f\x90\xb6. If your terminal is using Unicode with the encoding UTF-8, you’ll be able to [enter the emoji] for the search.

This demonstrates that you’re sending raw bytes over the network and they need to be decoded by the receiver to be interpreted correctly. This is why you went to all of the trouble to create a header that contains the content type and encoding.

Here’s the server output from both client connections above:

Accepted connection from ('10.0.2.2', 55340)

Received request {'action': 'search', 'value': 'morpheus'} from ('10.0.2.2', 55340)

Sending b'\x00g{"byteorder": "little", "content-type": "text/json", "content-encoding": "utf-8", "content-length": 43}{"result": "Follow the white rabbit. \xf0\x9f\x90\xb0"}' to ('10.0.2.2', 55340)

Closing connection to ('10.0.2.2', 55340)

Accepted connection from ('10.0.2.2', 55338)

Received request {'action': 'search', 'value': '🐶'} from ('10.0.2.2', 55338)

Sending b'\x00g{"byteorder": "little", "content-type": "text/json", "content-encoding": "utf-8", "content-length": 37}{"result": "\xf0\x9f\x90\xbe Playing ball! \xf0\x9f\x8f\x90"}' to ('10.0.2.2', 55338)

Closing connection to ('10.0.2.2', 55338)Look at the sending line to see the bytes that were written to the client’s socket. This is the server’s response message.

You can also test sending binary requests to the server if the action argument is anything other than search:

$ python app-client.py 10.0.1.1 65432 binary 😃

Starting connection to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Sending b'\x00|{"byteorder": "big", "content-type": "binary/custom-client-binary-type", "content-encoding": "binary", "content-length": 10}binary\xf0\x9f\x98\x83' to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Received binary/custom-server-binary-type response from ('10.0.1.1', 65432)

Got response: b'First 10 bytes of request: binary\xf0\x9f\x98\x83'

Closing connection to ('10.0.1.1', 65432)Because the request’s content-type is not text/json, the server treats it as a custom binary type and doesn’t perform JSON decoding. It simply prints the content-type and returns the first ten bytes to the client:

$ python app-server.py '' 65432

Listening on ('', 65432)

Accepted connection from ('10.0.2.2', 55320)

Received binary/custom-client-binary-type request from ('10.0.2.2', 55320)

Sending b'\x00\x7f{"byteorder": "little", "content-type": "binary/custom-server-binary-type", "content-encoding": "binary", "content-length": 37}First 10 bytes of request: binary\xf0\x9f\x98\x83' to ('10.0.2.2', 55320)

Closing connection to ('10.0.2.2', 55320)Troubleshooting #

Inevitably, something won’t work, and you’ll be wondering what to do. Don’t worry, it happens to everyone. Hopefully, with the help of this tutorial, your debugger, and your favorite search engine, you’ll be able to get going again with the source code part.

If not, your first stop should be Python’s socket module documentation. Make sure you read all of the documentation for each function or method you’re calling. Also, read through the Reference section below for ideas. In particular, check the Errors section.

Sometimes, it’s not all about the source code. The source code might be correct, and it’s just the other host, the client, or server. Or it could be the network. Maybe a router, firewall, or some other networking device is playing man-in-the-middle.

For these types of issues, additional tools are essential. Below are a few tools and utilities that might help or at least provide some clues.

ping #

ping will check if a host is alive and connected to the network by sending an ICMP echo request. It communicates directly with the operating system’s TCP/IP protocol stack, so it works independently from any application running on the host.

Below is an example of running ping on macOS:

$ ping -c 3 127.0.0.1

PING 127.0.0.1 (127.0.0.1): 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=0 ttl=64 time=0.058 ms

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=0.165 ms

64 bytes from 127.0.0.1: icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=0.164 ms

--- 127.0.0.1 ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0.0% packet loss

round-trip min/avg/max/stddev = 0.058/0.129/0.165/0.050 msNote the statistics at the end of the output. This can be helpful when you’re trying to discover intermittent connectivity problems. For example, is there any packet loss? How much latency is there? You can check the round-trip times.

If there’s a firewall between you and the other host, a ping’s echo request may not be allowed. Some firewall administrators implement policies that enforce this. The idea is that they don’t want their hosts to be discoverable. If this is the case and you have firewall rules added to allow the hosts to communicate, then make sure that the rules also allow ICMP to pass between them.

ICMP is the protocol used by ping, but it’s also the protocol TCP and other lower-level protocols use to communicate error messages. If you’re experiencing strange behavior or slow connections, this could be the reason.

ICMP messages are identified by type and code. To give you an idea of the important information they carry, here are a few:

| ICMP Type | ICMP Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0 | Echo request |

| 0 | 0 | Echo reply |

| 3 | 0 | Destination network unreachable |

| 3 | 1 | Destination host unreachable |

| 3 | 2 | Destination protocol unreachable |

| 3 | 3 | Destination port unreachable |

| 3 | 4 | Fragmentation required, and DF flag set |

| 11 | 0 | TTL expired in transit |

See the article Path MTU Discovery for information regarding fragmentation and ICMP messages. This is an example of something that can cause strange behavior.

netstat #

In the section Viewing Socket State, you learned how netstat can be used to display information about sockets and their current state. This utility is available on macOS, Linux, and Windows.

That section didn’t mention the columns Recv-Q and Send-Q in the example output. These columns will show you the number of bytes that are held in network buffers that are queued for transmission or receipt, but for some reason haven’t been read or written by the remote or local application.

In other words, the bytes are waiting in network buffers in the operating system’s queues. One reason could be that the application is CPU bound or is otherwise unable to call socket.recv() or socket.send() and process the bytes. Or there could be network issues affecting communications, like congestion or failing network hardware or cabling.

To demonstrate this and see how much data you can send before seeing an error, you can try out a test client that connects to a test server and repeatedly calls socket.send(). The test server never calls socket.recv(). It just accepts the connection. This causes the network buffers on the server to fill, which eventually raises an error on the client.

First, start the server:

$ python app-server-test.py 127.0.0.1 65432

Listening on ('127.0.0.1', 65432)Then run the client to see what the error is:

$ python app-client-test.py 127.0.0.1 65432 binary test

Error: socket.send() blocking io exception for ('127.0.0.1', 65432):

BlockingIOError(35, 'Resource temporarily unavailable')Here’s netstat output from while the client and server are still running, with the client printing out the error message above multiple times:

$ netstat -an | grep 65432

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address (state)

tcp4 408300 0 127.0.0.1.65432 127.0.0.1.53225 ESTABLISHED

tcp4 0 269868 127.0.0.1.53225 127.0.0.1.65432 ESTABLISHED

tcp4 0 0 127.0.0.1.65432 *.* LISTENThe first entry is the server (Local Address has port 65432):

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address (state)

tcp4 408300 0 127.0.0.1.65432 127.0.0.1.53225 ESTABLISHEDNotice the Recv-Q: 408300.

The second entry is the client (Foreign Address has port 65432):

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address (state)